Henry ford pictured in 1919, a year before he visited galt

The day Henry Ford came to Galt

By David Menary

At the time of his death, on April 30, 1950, Dr. Harry MacKendrick was regarded as the dean of Galt physicians.

In the late autumn of 1915, Dr. Harry MacKendrick, a Galt physician, was overseas as a surgeon during World War I when he got a disturbing telegraph. The cable was as sudden a shock as anything the war offered, telling him his wife, Janet Wishardt (nee Carter) was seriously ill and he should make his return voyage to Galt as soon as possible.

When he arrived home, in December 1915, she was near the end. She died three days later.

It was a devastating blow for the doctor, but he was gratified to be at her side when the end came.

“After getting things straightened out, I went back again as my only son, Harry, had enlisted in the local 111th battalion and was shortly going overseas.

Dr, Harry Mackendrick

Chance encounter led to long friendship

While waiting for his boat in Halifax he met a Dearborn, Michigan-area man by the name of Henry Ford. The two both waited several days for the same boat to take them to England. They soon became fast friends.

“He was sending over a group of his head men in different departments to show the British how to build tractors,” said MacKendrick. “They took patterns and castings.”

Ford found MacKendrick, a former world champion canoeist, to be a man of substance. They were nearly the same age, and both were accomplished, though Ford’s fame was worldwide by then. Both Ford and MacKendrick got their start in machine shops, and both were ambitious.

“We were together at Halifax for four days and Mr. Ford and I used to go for long walks (we were waiting for a boat), and became well-acquainted. He made me promise that when I came back I would go over to Detroit and visit him, which I did.”

Ford, who was actually three years older than MacKendrick, took a liking to his new Canadian friend. MacKendrick told him he owned the first Ford car — indeed, the first car — in Galt. That car was a Model C, a car Ford marketed for doctors making house calls.

Ford was known for his pacifism during the first years of World War I. He introduced the Model T on October 1, 1908, with the steering wheel on the left, a pattern that every other automobile manufacturer in North America soon copied.

By the time MacKendrick, who had celebrated his 50th birthday while overseas, visited Ford in Dearborn, fully half of all the cars in America were Model T’s.

Ford explained the colour scheme of his cars in his autobiography. “Any customer can have a car painted any colour he wants as long as it is black.”

two famous men

MacKendrick visits Ford at Dearborn

Ford gave MacKendrick a tour of his works at Highland Park. A little over a decade later he would give Lindbergh a similar type of tour after the aviation pioneer was celebrated around the world for his epic solo flight across the Atlantic.

Ford also visited MacKendrick in Galt, following MacKendrick’s visit to Dearborn.

“A year later,” said MacKendrick, ”he called on me when I lived downtown.”

It was a quiet Sunday, on the afternoon of August 29, 1920, when Ford came to see MacKendrick. He was with a party of six, en route to the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. He slipped into Galt unannounced, and no media was present for the visit by one of the world’s most celebrated men. A day later the Galt Reporter ran a short article about Ford’s visit.

It may not have been the first time Ford came to Waterloo County. Ford was rumoured to have visited Kitchener when it was called Berlin, in the first decade of the 20th century. Ford’s alleged visit to Berlin had long been a rumour in the KW area, but a May 3, 1939 Record story examined the legend and weighed the evidence.

MacKendrick was born in Galt in the 1860s

The tale of Henry Ford in Waterloo County

By then, a couple of generations had related the story by word of mouth, but no living person could recall Ford being in town. It was said that Ford attempted to establish an auto manufacturing plant in Berlin around 1900, which pre-dated the beginning of his successful career in Detroit.

Dearborn and environs were his hometown, and is today still the seat of the Ford empire.

“About the time of his appearance in Berlin,” said the Record story, “Mr. Ford was making a valiant attempt to raise money for his ’fantastic’ venture and it is on this feature of his life that the legend is based.”

Ford supposedly came to Berlin to sell his idea to local businessmen, but evidently, if that indeed was the case, his pitch fell flat. Records at the Henry Ford Museum are scarce for the early part of Ford’s career; there is no supportive evidence to give credence to the Berlin legend.

The Record says that one of Ford’s biographers mentions an attempt to start a business in Canada, but does not elaborate. Although there were plenty of people in Berlin who related the Ford story, giving some sense that there must have been something to it, in the end, all we have is a legend.

McKendrick bought first car before he knew Ford

Ford went on from Galt to visit the CNE

But Ford’s visit to MacKendrick in Galt in 1920 is fact, as was noted in the Monday edition of the local Galt newspaper.

At the time, the CNE was the largest annual fair in the world, with world-class industrial and agricultural exhibits. Ford loved it.

With Ford that day was native-born Detroiter Ernest Liebold, a banker who began his career as bank messenger before becoming cashier of Henry Ford’s Highland Park State Bank. Eventually he became Ford’s general secretary with responsibility for essentially all of Ford’s business activities outside of Ford Motor Company.

Also with Ford that day in Galt was the distinguished Gordon McGregor, founder and head of Ford Motor Company of Canada, Limited. A Windsor native, McGregor’s father was William McGregor, president of the Walkerville Wagon Company Limited in Walkerville (Windsor) Ontario. He took over the management of the company in 1901 and, on the death of his father in 1903, became president.

At a meeting with his brothers, Walter and Donald, in January 1904, Gordon McGregor said:

“There are men in Detroit who say every farmer will soon be using an automobile. I don’t see why we cannot build them here in the wagon factory.”

After meeting with Ford early on, he got a personal agreement from Ford to form and finance a company to manufacture and sell Ford products in Canada.

Model C is a rarity today

MacKendrick gave Ford his first and last glass of whiskey

Other than the Reporter story from 1920, there does not appear to be a record of the visit in any of the surviving Ford papers, though MacKendrick mentions the visit in his unpublished and brief autobiography.

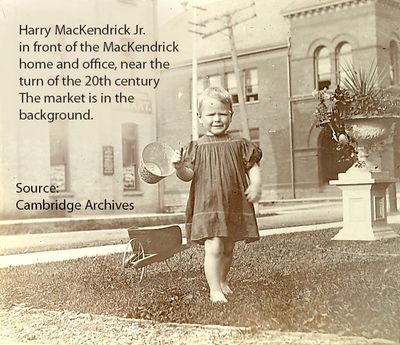

Ford, a teetotaller, evidently had his first, and last drink of whiskey at MacKendrick’s house that afternoon. MacKendrick’s house also doubled as his medical office and still survives though it looks different today, 102 years after Ford’s visit. It is located on the southwest corner of the Dickson and Ainslie intersection, kitty corner to the market building.

In 1903, and for several years afterward, that’s where Dr. MacKendrick parked his first—and Galt’s first—automobile, and where his son grew up.

- Copyright © 2022 It happened in Cambridge - All Rights Reserved.